The campus of the San Francisco Art Institute in Russian Hill was designed in the 1920s by Bakewell and Brown, architects of the nearby City Hall and Coit Tower. Later in 1969, Paffard Keatinge-Clay, who had worked in Le Corbusier’s atelier in 1948, designed its addition. He’s also known to have worked in Mies van der Rohe’s office and apprenticed years earlier with Frank Lloyd Wright.

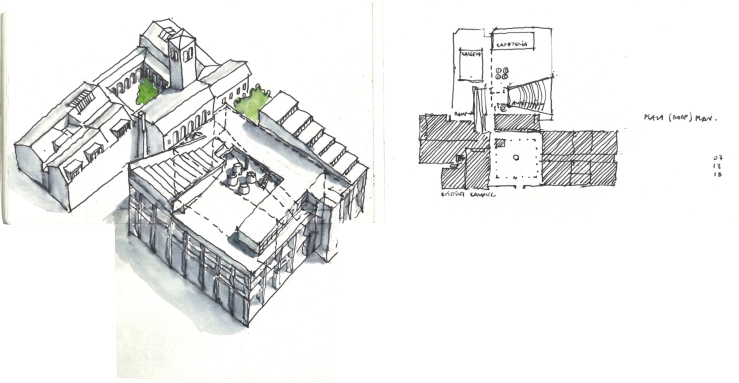

The new building’s program consisted of additional art studios, classrooms, faculty and administrative offices, an auditorium, gallery spaces, a cafeteria, and outdoor spaces, among others. Due to an abrupt change in topography, the addition sits below the existing complex’s main level except for its roof terrace, where the auditorium, cafe, and gallery spaces are located.

The structure resembles Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center at Harvard, with its béton brut surfaces, ample ramps, light canons, and brise soleils being integral elements of the composition.

However, in contrast to its East Coast precedent, one could argue that at Keatinge-Clay’s building, there are far fewer poetic licenses employed. For example, at the Carpenter, a pedestrian ramp that cuts through the building allows for a way to traverse the structure, producing what Le Corbusier called an architectural promenade. The ramp as part of the spatial sequence is, in fact, one of the highlights of the Carpenter, offering — in some instances — unobstructed views of the interior spaces, art galleries, and studios.

However, once one carefully studies it, the through-block connection seems — in my opinion — a bit gratuitous since there is not much happening on the other side of the block, and you are just feet away from the corner. The main landing only allows access to a secondary entrance and ancillary programs. Also, the secondary nature of the entrance, which most of the time remained closed to the public, stresses its excessiveness.

In contrast, the ramp at the Art Institute, albeit not as sculptural as the Carpenter’s, yet indispensable, not only stitches the interior spaces of the addition with the existing main building but also serves as a connection that allows views into the interior spaces and bridges the abrupt change in topography.

The buildings’ treatment of the roof terraces contrasts significantly as well. At the Carpenter, the roof terrace or fifth façade is enjoyed solely by a private apartment for visiting faculty/artists. In Keatinge-Clay’s addition, the toit-jardín is –in contrast — the project’s hierarchical space. In true emulation of Le Corbusier’s ideas, the roof terrace at the Art Institute becomes a public square, a gathering space where multiple activities occur simultaneously.

The main space of the terrace (represented on the last sketch and axonometric above) is enclosed on three sides by the auditorium, an indoor and outdoor gallery space, and the cafeteria. The terrace openness contrasts with the enclosed nature of the main courtyard at the 1920s building next door. Keatinge-Clay’s roof terrace frame panoramic views of the city’s waterfront below

Also, the roofs over the external gallery, cafe, and auditorium become accessible terraces and not only provide additional vantage points of the city but also allow for a diverse array of activities to occur simultaneously.